The Girmit narrative is no longer concerned with the grand moral questions of indenture, with questions of right and wrong, and with apportioning blame.

The Girmit narrative is no longer concerned with the grand moral questions of indenture, with questions of right and wrong, and with apportioning blame.

Among a newer generation of scholars, the appeal of the ‘Tinker’ thesis has dimmed.

The latest dissension from the slavery thesis comes from Trinidad’s Gerard Tikasingh who rejects ‘the mythic ideas that indentured immigration was some form of disguised slavery.’ Indenture, he argues, was ‘a contract for a five-year term of service, for which the worker was paid. It was a contract for a term of service, not involving the ownership of a person.’

Violence and brutality in the system are readily conceded but the diverse experience in different places is also acknowledged.

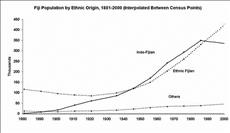

Fiji was not Guyana or South Africa.

There was change over time.

Greater agency is accorded to the Girmityas in the making of their own histories.

New identities

Emphasis in the literature has now shifted to the actual lived experience of indenture, the ways in which men and women from a variety of social and economic backgrounds coped with the demands made on them, raised families, formed communities and forged new identities from fragments of the new and the old.

Emphasis in the literature has now shifted to the actual lived experience of indenture, the ways in which men and women from a variety of social and economic backgrounds coped with the demands made on them, raised families, formed communities and forged new identities from fragments of the new and the old.

In Fiji at least, indenture was not a life sentence that lasted decades as it was in some other places, but a limited detention of five or at most ten years after which the freed Girmityas set up on their own in settlements of leased or privately acquired lands.

If it was slavery, it was slavery with a definite sunset clause

This, then, is the latest Avatar of the Girmit narrative, but it struggles to find full acceptance in the popular imagination.

Nuance, qualification and subtlety do not travel as well as sharp images and views simply presented in stark, easily-grasped words. That, I suppose, is the fate of scholarly discourse in the public arena.

But at least, Girmit is no longer an experience languishing in the shadows, a cause for shame and embarrassment. It has become a household word among Indo-Fijians, and many indigenous Fijians have also heard of ‘Girmiti.’

Political rivals

During the 2004 celebrations marking the 125th anniversary of the arrival of Indians to Fiji, it was interesting to observe two rival groups, aligned to two different Indo-Fijian political parties. The Fiji Labour Party and the National Federation Party published separate glossy pamphlets full of pictures and stories about the past and potted biographies of prominent individuals and organised rallies and ceremonies.

During the 2004 celebrations marking the 125th anniversary of the arrival of Indians to Fiji, it was interesting to observe two rival groups, aligned to two different Indo-Fijian political parties. The Fiji Labour Party and the National Federation Party published separate glossy pamphlets full of pictures and stories about the past and potted biographies of prominent individuals and organised rallies and ceremonies.

Subtly, each was accentuating the role and contribution of its own selected heroes, each claiming to be the proper inheritor of the legacy of Girmit. Some used the occasion to differentiate the descendants of the ‘pioneer’ Indians who came under indenture from the free migrants who came later, as Girmityas and Non-Girmityas. This has long been a refrain in Indo-Fijian political discourse and the politics of inclusion and exclusion.

Political edge

The commemoration of Girmit has acquired a political edge in recent decades as Fijian nationalists have tried to disinherit the Indo-Fijian community of their political rights.

Subtly, the Girmit experience is transformed into a serviceable ideology to demand equal rights for the descendants of the Girmityas, not as a matter of grace from the powers-that-be, but as a matter of birth right:

‘We have earned our right to belong to this country as full citizens. This is our home, too. We are not here on the sufferance of others. Our existence here is non-negotiable.’

Generations cast from my seeds/will clasp their hands and say/our ancestors carved those fields/which have given us meanings/meanings to stand tall/This land is ours too (Monar, 1998:203).

The quest for acceptance and equality is both legitimate and necessary, but it clashes with another powerful claim: the claim to paramountcy by indigenous Fijians, on the assumption that as the first settlers in the land, their rights, interests and concerns deserve privileged consideration. The paramountcy versus parity paradigm keeps the Girmit experience as an ideological platform at the forefront of Indo-Fijian political discourse.

Girmit beyond Fiji

Remembering Girmit is no longer confined to the Indo-Fijian community in Fiji.

The Girmit narrative has taken a different turn in recent decades with the increasing size of the Indo-Fijian diaspora in North America, Australia and New Zealand.

There is a palpable sense of the need to know in the new generation growing up in these places. Hardly a week goes by when I do not receive a request from a complete stranger, usually a younger person (often a university student), for information about their roots in India. The need to know is deep and genuine, but the quest often remains unrealised because the information about their ancestors (their district of origin, the name of the ship on which they came, the approximate date of migration) is incomplete.

Some younger investigators have made documentaries or short films about their journeys back. Others have written poems, short stories and songs about the Girmit experience, repeating the popular rendition of the past.

Inadequate exploration

But so far, we do not have an extensive literary exploration of the indenture experience, the sole exception being Jogindar Singh Kanwal’s Hindi novel ‘Savera’ (Dawn). Fiji has not yet produced an Abhmanyu Anath (of Mauritius), author of the great novel ‘Lal Pasina’ (Bloody Sweat), although Subramani’s ‘Dauka Puran’ about the post-indenture period in Fiji is a signal achievement.

Fiji compares very poorly with the literary efflorescence of the Indo-Caribbean where novelists, writers of short fiction, poets and playwrights have long been engaged in a massive literary reconstruction of their past. Much of the best Indo-Fijian literary effort is focused on the contemporary period, some of it in incongruous post-colonial mode.

Electronic media

In keeping with the times, the electronic media has entered the scene.

Several websites (Fijigirmit.org, Girmitunited.org) provide access to raw historical data as well as published pieces about various aspects of indentured migration and settlement in Fiji. This is to be welcomed; it is the way of the future.

The Internet and the visual media will become the new frontiers where the future narrative of Girmit will be written and debated. The Internet will reach far larger audiences than the print media can ever hope to match.

Negative effects

But there is a negative side to this as well. The internet has sometimes become the vehicle for the propagation of private opinion, which passes for scholarship.

Emotion overrides thought and reasoned debate.

Often it is a case of ‘My mind is made up, do not confuse me with facts.’

I know of some fairly desperate people being encouraged to apply for an Australian immigration visa and demand sympathetic consideration on the grounds that their ancestors toiled for the CSR Company. No chance there.

Some advocate compensation from the British Government for the sufferings that Indian people endured under indenture (Goundar, 2011: 39).

This is an emotionally appealing cause but legally futile.

No legal right

The labourers came under a contract and jettisoned the right to return when their indentures expired and war-interrupted shipping resumed.

Not everyone wanted to return either.

‘Most of us regard Fiji as our permanent home,’ Indians had told the Secretary of State for the Colonies in December 1927 (Gillion, 1977:105).

More than a century later, why would the British Government pay compensation: to whom and how much?

This is a microcosm of a much larger problem of the cyber age: anything goes, at the expense of discrimination and a serious quest for accuracy based on painstaking research.

Instant gratification is the order of the day.

Respecting Girmityas

In one important respect, things have changed. The Girmityas are no longer viewed as objects of contempt and pity as they had been in the late 19th and early 20th centuries or as curious, irrelevant oddities for a generation or two after the end of indenture.

They are now figures of reverence in the Indo-Fijian imagination, people from impoverished, improbable backgrounds who achieved great things in the face of very great odds.

Their resilience and resourcefulness are celebrated in public discourse.

Mythic figures now, they represent nothing less than the triumph of the human spirit over adversity. It has been a long time coming.

Former Fiji Indian leader Jai Ram Reddy catches the current consensus of opinion in an undated speech on the occasion of a Girmit celebration as follows:

‘The Girmityas gave meaning to the ideals of hard work, perseverance, commitment and endurance, and provided the example and inspiration for subsequent generations to emulate. That is the lasting legacy of Girmit and the Girmityas.’

And it is well worth commemorating.

Professor Brij Lal is Professor of Pacific and Asian History at the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, Canberra. The above is an excerpt of his new publication due later this year.

Professor Lal will be in Auckland to speak at the Girmit Anniversary celebrations being organised by the Fiji Girmit Foundation of New Zealand on Sunday, May 18, 2014 at Skipton Hall, 53 Skipton Street, Managere, Auckland. The event, commencing at 130 pm is open to all.