The biggest democracy in the world is facing challenging times.

The common man’s disdain and apathy towards the political system in India has reached its zenith.

A prime example of this was the widespread support given to the campaign against corruption run by social activist Anna Hazare.

Looking at the landscape of Indian politics today, the notion of politicians gaining back the trust of the populace seems a farfetched idea.

This is worsened by the fact that Indian politics increasingly resembles a closed shop; being run by a select group of dynasties.

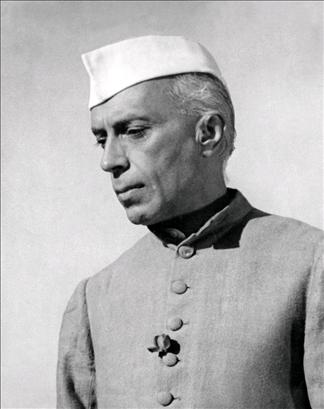

The first example of dynastic politics dates back to the 1960s, when Independent India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru gave his daughter Indira Gandhi a ticket to contest from the city of Raebareli, after the death of her husband Feroze Gandhi.

Growing dynasty

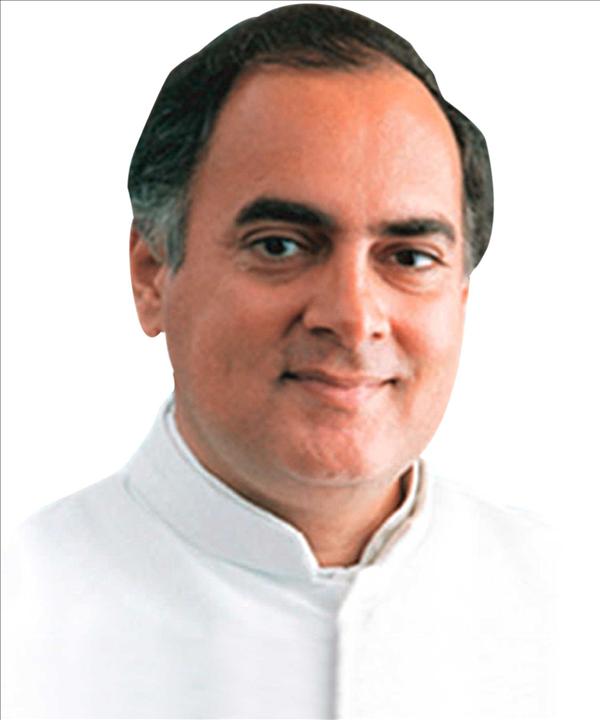

Mrs Gandhi became the Prime Minister, groomed her second son Sanjay Gandhi to be her political heir but his untimely death and the unwillingness of her elder son Rajiv Gandhi seemed to end the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty.

But fate had a different design. Following her assassination on October 31, 1984, Rajiv was forced into power and his assassination on May 21, 1991 brought his once-shy wife Sonia to limelight. She is today an elected member of the Lok Sabha (Lower House), President of the Congress Party and de facto Prime Minister. It would not be long before her son Rahul, who is also an elected Member of Parliament and General Secretary of the Congress Party is chosen to rule the country as the Prime Minister.

Sanjay Gandhi’s wife Maneka was a minister in the Bharatiya Janata Party government and their son Varun is today a Member of Parliament.

The Nehru-Gandhi dynasty is set to expand.

The imponderables

This trend has only gained momentum, and has become the unwritten norm, with most politicians feathering their own nest.

Students of Indian politics find it hard to fathom as to why such a phenomenon occurs in a country of immense political awareness and intense media coverage.

Have Indians given up on the political systems and politicians? Have they lost interest in elections, or have they resigned to the fact that any political leader will be as good or bad as the previous one?

Answers to these are not easy to find.

Power is intoxicating and hence most people hesitate to give it up.

The mentality of most politicians is to keep it within the family; preferably with their children.

A perfect launch pad is provided for these wards, and they are parachuted to the top echelons of their parent’s parties.

The goodwill of their parents and the solid backing of their parties election machinery results in their comfortable election victories.

The challenges

Challenges of course follow, with political and other pressures looming large.

These young politicians have the onerous task of being more than props advocating a young face for their parties. They must deliver results on the ground and strengthen their organisations.

Even after inducting them into mainstream politics, in many cases their parents are hesitant to bow out gracefully from the political arena.

This is against the wish of the people who would like to test the leadership quality and administrative ability.

As far as the regional parties are concerned, this acts as a deterrent to the aspirations of grassroots workers, as they see their parties being slowly turned into private run companies, where a select clan runs the party, and meritorious lower rung leadership gets relegated.

This trend is not confined to politics.

All professions are littered with examples of wards following in the career paths their parents have traversed.

At the end of the day, it depends on the merits of the new generation and its abilities and ambitions.

They are often in a dilemma, deciding whether to continue on the path of their parents or follow a new path with emerging opportunities.

Indian democracy is at crossroads and it is only the people (and not politicians).