Deepawali or Diwali is a Festival that remains as the richest commemoratory jewel in the Hindu pantheon.

It is associated with the origins of Hinduism as both ‘Padma’ and ‘Skanda Purana’ allude to it as a Festival in which the ‘Diyas’ symbolise the Sun, the source of light and energy for all life. Its beginnings are traceable to the ancient times when Homo sapiens had transitioned from pastoral nomads to a more homogenous agricultural pursuit.

The beginning

Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa (now in Pakistan) in 1920s and more recent ones in Lothal, Kuch region and other areas in India indicate that the people celebrated their harvest, befitting their open classless and casteless society.

It was during this era that the solar symbol, ‘Svastika (Swastika) was revered for its positive significance in the ‘wheel of life’ until it was demonised by the victors of the World War II to scorn the Nazis for using it as the vehicle of their conceived nativity and power.

The elemental beginnings soon embraced legends that led to evolution of beliefs and symbols such as the marriage of Goddess Lakshmi to Lord Vishnu and worshipping of the Elephant-headed Ganesha.

The elemental beginnings soon embraced legends that led to evolution of beliefs and symbols such as the marriage of Goddess Lakshmi to Lord Vishnu and worshipping of the Elephant-headed Ganesha.

Lakshmi was idolised for Prosperity and Ganesha for Auspiciousness.

The former appealed to the business class and the latter curved His niche among the innocuous devotees. In Mumbai, during the 1960s and 1970s, the ceremonial immersion of Ganesha was more popular than Diwali itself and today the Ganesha Mantra is an essential part of all Hindu marriage celebrations.

Vedic Period

A significant change occurred at the time of the Aryans and Mauryans when the kings were capped with the blessings of the priests that gave rise to Brahmanism.

In the Vedic period (1500-500 BCE) use of the sacrificial fire for ‘yags’ and ‘hawan’ became the norm. Nirad Chaudhuri writes in his ‘The Continent of Circe’ that there were enormous intake of ambrosia soma (intoxicant) and indulgence in food consumption, especially meat of all kinds, including beef.

Deepawali was said to be celebrated in all its splendour on the return of Lord Rama from exile (vanvas) of 14 years and coming back of the Pandavas from their 12 years of banishment. Alas, during my recent visit (2008) to Ayodhya, I could not find even a symbolic existence of the Janaka kingdom.

At the end of the Vedic period, India gave rise to Buddhism and Jainism. The latter sect embraced Deepawali to commemorate Lord Mahavira’s attainment of Nirvana (eternal bliss). Buddhism was a more austere creed aimed at solemn pursuit of oneness with God.

It therefore lost much of the royal patronage and after the Mauryans, Brahmins ruled the roost until after Independence when they had to rejig their status in the new environment of freedom.

Secular credentials

While the reform movements such as the Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj assailed the social ills such as the sati, thuggee, dowry and caste systems and the pernicious practices choreographed by the Brahmins, their critique did not include the age-old Festivals such as Diwali, Vaishakhi, Onam and Pongal.

As a ‘secular’ Festival, Diwali is celebrated by Hindus, Jains and Sikhs and in their own ingenious formats by the Christians, Buddhists and Sufi Muslims. Its liberal message is imbedded in the victory of light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, good over evil and hope over despair.

The Arya Samajists dedicate Deepawali in honour of Swami Sarawati’s birthday and the Sikhs observe the return of Guru Hargobindji. On this day, the Newar Buddhists (of Nepal) glorify the acceptance of Buddhism by Ashoka the Great.

Philosophical plinth

However, for an agnostic or atheist, the philosophical base of such Festivals are paramount as they meditate or contemplate the infinite transcendental reality, the ‘Atman’ that is above body and mind.

Hindus celebrate a myriad of colourful Festivals linked to the birth of Gods such as Rama (Rama Navami), Krishna (Gokulashtami or Krishna Ashtami) and seasonal celebrations such as ‘Holi’ and Deepawali.

The symbols that have stood the test of time are Swastika, Aum, Chakra (disc) and Lotus. Thus, Deities, Symbols, Pilgrimages and Festivals are part of the colourful panorama of Hindu life.

Normally, four days are devoted to Deepawali, each with its own legendary tales and myths. Although for Hindus they have deep religious bearing, they are nonetheless unauthenticated ‘bardic tales.’

Editor’s Note: The Four Days of Deepawali have been described in the article, ‘Indifference to customs negates the festive spirit’ appearing in this Special Report.

Myth busters

Bursting of firecrackers is believed to provide awareness of the plentiful and blissful state of human beings. A more scientific explanation is that they disperse the insects, mosquitoes and wild bird and animals that abound in the post-monsoon season.

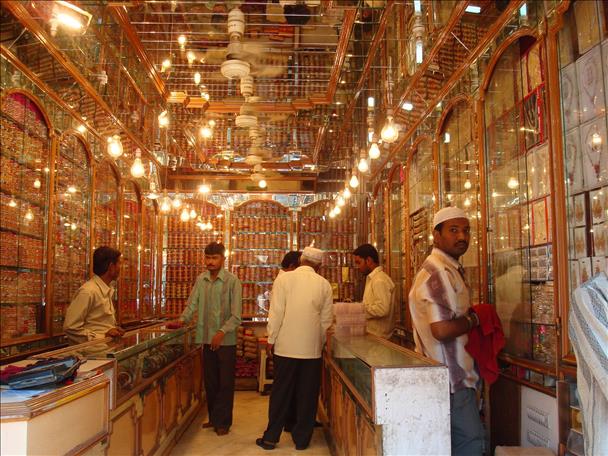

Prior to the Brahmanical order in the Vedic era, Deepawali was a joyous occasion, a celebration of feasting, fashionista and fun. The tradition of gambling was pinned to the legend that Parvati played dice with Shiva on this day. Its linkage with wealth and prosperity saw the celebration of ‘Dhan Teras’, particularly by the well-off sections of the community.

In Fiji, the People of Indian Origin (PIOs) were not aware of ‘Dhan Teras’ until they migrated to New Zealand, Australia, Canada and US.

Like ‘Dhan-Teras’, Rangoli was not the tradition of the ‘Girmityas’ (indentured labourers) in the sugar colonies. Its use in western adoptive countries has provided the scope for up scaling traditional art form.

Impact outside India

In many countries outside India, Deepawali is a crucible of identity for all South Asian people. That it is a recognised public holiday in Mauritius, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Fiji, Malaysia, Singapore and Suriname speaks of the invaluable contributions of the Indian community.

Deepawali maintains its holiday status in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

The festivities are enmeshed in the cobweb of assumed puritanical restrictions and commercial intent. Do not despair. If you are unable to be part of the rituals and chants, retire in solitude, light a Diya, shut your eyes and contemplate on the Supreme.

That is where your enlightenment is. That is the relevance of Deepawali.

Mahendra Sukhdeo is author of ‘Aryan Avatars- From prehistoric Nomads to Settlers in the Pacific.’ He was earlier an academic, politician and trade unionist in Fiji. He was a Founder-Vice-President of the Fiji Labour Party and served as the Deputy Lord Mayor of Suva during the tumultuous years of 1987-1988. He now lives in Melbourne, Australia. Email: mahendranz@yahoo.co.nz